Bubonic Plague if It Hit Again Quora

An epidemic of the bubonic plague usually called The Plague or (since the late 16th century) the Blackness Expiry killed millions in Europe and many parts of Asia between 1347 and 1352. The plague was spread and transmitted past rats and other rodents, who carried infected fleas in their fur, just this cause was non known at the fourth dimension.

Nigh 20 one thousand thousand of the 60 million people in Europe at the fourth dimension died. In all of recorded history, this epidemic has only two rivals: the plague of 542 and the flu epidemic of 1918. The long term furnishings affected the economy by causing a long-term labor shortage.

Symptoms

The germ theory of illness had not been discovered, so the means of transmission and cure were a mystery to contemporary doctors. Afterwards the 3-7 day incubation flow, the sufferer would experience initial symptoms of chills, fever, diarrhea, headaches, and the swelling of the infected lymph nodes. If it was untreated, xxx-75% of those who contracted the plague died.

Amongst the most prominent signs of the disease were the evolution of blackish colored swellings chosen "buboes."

Spread

It spread rapidly forth trade routes and specially the Silk Road. It originated amongst the Mongols in Asia, who allowed their sacks of food to exist exposed to rats and fleas that carried the fatal disease. Traders brought it with them into the Centre E, Northward Africa, and Europe. In 4 short years, a third of Europe'due south population was lost to the plague, especially the poor.

Slow recovery

The fatality rate was even higher in China, where an estimated 25 million died from it. It took 100 years for Europe and Cathay to recover, and a longer menstruation of time for Islamic countries and the Middle East. Egypt was striking particularly difficult, with some areas non recovering for 500 years.

Impact on economic system

The era of the Black Death witnessed a series of important long-term changes in demographic behavior, agriculture, manufacturing, trade, and engineering science. Existent wage series reverberate the productivity increases from these changes and suggest that the Low Countries and England were able to resist to a greater extent the general trend for wages to reject during the 2d leg of the demographic wheel that began with the Black Expiry. A wage gap thus began to emerge between the northwest and the residual of the continent after 1450.[1]

The devastation of the serfs, who fabricated up the vast majority of the population, also strengthened their socio-economic position. The scarcity of labor meant that, through proto-strikes, they could bargain with state-owners to ameliorate their conditions of life. This led to the beginning of the end of feudalism in Europe, as it weakened the force behind the success of the manors. The plague also created a need for more centralized government that could answer effectively to disease.

The Blackness Decease spurred monarchies and city-states across much of medieval Europe to formulate new wage and price legislation. These legislative acts splintered in a multitude of directions that to date defy any obvious patterns of economic or political rationality. A comparison of labor laws in England, France, Provence, Aragon, Castile, the Low Countries, and the city-states of Italy shows that these laws did not flow logically from new post-plague demographics and economics - the realities of the supply and demand for labor. Instead, the new municipal and majestic efforts to command labor and artisans' prices emerged from fears of the greed and supposed new powers of subaltern classes and are meliorate understood in the contexts of anxiety that sprung forth from the Black Death's new horrors of mass bloodshed and destruction.[2]

Popular response

Feet levels were very high—death was at hand for everyone. One issue was social behavior such as the flagellant movement and the persecution of Jews, Catalans, and beggars. In some regions such as Alsace the Jews were blamed and were driven from the primary cities.

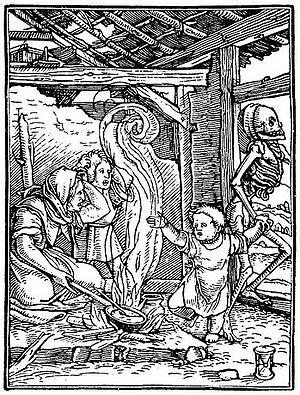

Artists often depicted the mass trauma using iii popular cultural representations that surfaced in performance, poetry, and painting: the Triumph of Expiry, the Dance of the Expressionless ("danse macabre"), and Death and the Maiden. The story and image of St. Sebastian became pop; the arrows with which he was pierced represented the plague, merely he survived the mortiferous attack and became a protector against the plague.

The Plague was commonly interpreted by popular religiosity as a divine penalisation despite some efforts to care for the disease medically. The theological interpretation viewed premature decease by the plague as either God's rescue of His own from unmitigated evil or as punishment for the victim's sins. Other interpretations blamed the plague on evil lifestyles or, in the example of Bavarian doc, humanist, and astrologer Joseph Grünpeck (d. 1532), on unfavorable juxtapositions of the heavenly bodies. Piety, contrition, and repentance were recommended equally therapies, forth with intercessory prayer by the saints and sometimes even exorcisms and magic. Natural remedies included treatment with garden herbs. Intended for both physicians and literate society at big, the treatises indicate a close relationship between applied piety and natural-empirical treatment - something Dutch historian Johan Huizinga called "the almost irreconcilable contradictions" of late medieval religious life.

Public health

Modern methods of disease control originated in response to the Plague. Cities such as Venice created public health boards to use sanitation, quarantine, and isolation to slow the spread of the plague. Gradually these early boards became permanent fixtures and ofttimes employed elaborate inspectorates to identify possible disease sources. These boards spread slowly to northern Europe, with the commencement wellness boards actualization in French republic only in 1580. Before long northern Europe began to implement health measures on a national calibration, such equally the 1709 Prussian regulations on dealing with the plague. Such measures culminated in the Habsburg 'cordon sanitaire,' a g-mile, guarded border in the Balkans in consequence from 1770 to 1871 to insulate the empire from epidemics common in the Ottoman Empire. These national endeavors tended to be more effective in dealing with large outbreaks of plague and other such diseases, just local measures retained their effectiveness confronting other owned diseases.[3]

Today

The bubonic plague is still endemic to some parts of the earth, such equally Tanzania.[4] In May 2007, there was an outbreak of the bubonic plague amongst animals in Denver, Colorado.[5] Nonetheless, due to mod sanitation in European countries, it is unlikely to ever achieve epidemic proportions once again. [6]

Farther reading

- Cantor, Norman. In the Wake of the Plague: The Black Decease and the World It Made (2002) excerpt and text search

- Clark, James M. The Trip the light fantastic toe of Death in the Middle Ages and Renaissance (1950), 131pp

- Cohn, Samuel. "The Black Death: End of a Paradigm", American Historical Review 2002 107(iii):703–738

- Gottfried, Robert S. The Black Death: Natural and Human Disaster in Medieval Europe (1985) excerpt and text search

- Hollar, Wenceslaus. The trip the light fantastic toe of death (1804) 70pp; art history full text online

- Huppert, George. After the Black Death: A Social History of Early Modern Europe (1998) excerpt and text search

- Naphy, William K., and Andrew Spicer. Plague: Blackness Death & Pestilence in Europe (2004)

- Platt, Colin. Male monarch Death: The Black Expiry and Its Aftermath in Belatedly Medieval England (1996) 262pp. excerpt and text search

References

- ↑ Sevket Pamuk, "The Blackness Death and the Origins of the 'Great Divergence' Beyond Europe, 1300-1600," European Review of Economic History 2007 11(3): 289-317,

- ↑ Samuel Cohn, "After the Blackness Death: Labour Legislation and Attitudes Towards Labour in Late-Medieval Western Europe," Economic History Review 2007 lx(three): 457-485,

- ↑ Gary B. Magee, "Disease Management in Pre-industrial Europe: A Reconsideration of the Efficacy of the Local Response to Epidemics," Journal of European Economic History 1997 26(3): 605-623,

- ↑ http://news.yahoo.com/s/afp/20070517/hl_afp/tanzaniahealthplague_070517161454

- ↑ https://www.cnn.com/2007/U.s.a./05/21/bubonic.plague.reut/alphabetize.html?department=cnn_latest

- ↑ http://wcbstv.com/national/topstories_story_142072816.html

Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/Bubonic_plague

0 Response to "Bubonic Plague if It Hit Again Quora"

Post a Comment